Emily Z. Keung, MD

Clinical Fellow

Complex General Surgical Oncology

Department of Surgical Oncology

University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Houston, TX

Charles M. Balch, MD

Professor, Department of Surgical Oncology

University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Houston, TX

Jeffrey E. Gershenwald, MD

Professor, Department of Surgical Oncology

Medical Director, Melanoma and Skin Center

University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Houston, TX

Allan C. Halpern, MD

Chief, Dermatology Service

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

New York, NY

The seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for cutaneous melanoma was implemented in 2010 following its introduction in 2009.1,2 In 2016, the Melanoma Expert Panel revised and published the eighth edition of the AJCC melanoma staging system, which was formally implemented nationwide January 1, 2018.

Based on analyses of a large international melanoma database, key changes have been made in the new system to improve staging and prognostication, risk stratification and selection of patients for clinical trials. With the ever-growing list of increasingly effective treatments available today, it is more important than ever to stage patients accurately so that the monotherapies and combination therapies approved across different stage levels can be used most effectively, and patients can be optimally informed about their options and considered for the most promising and appropriate clinical trials.

Here, we have distilled the most important changes in the new AJCC melanoma staging system, adapting them from the chapter on cutaneous melanoma in the eighth edition and the recently published analyses of the international database by the Melanoma Expert Panel.3,4

Change |

Summary of Change |

| Determinants of Primary Tumor (T) Status | Primary melanoma thickness and ulceration continue to define T category strata, but tumor thickness is to be measured to the nearest 0.1 mm, not the nearest 0.01 mm. The definitions of T1a and T1b have been revised so that T1a melanomas include those <0.8 mm without ulceration while T1b melanomas include those 0.8-1 mm with or without ulceration and those <0.8 mm with ulceration. Mitotic rate is no longer a T1 category criterion but should be documented for all invasive primary melanomas. |

| Determinants of Regional Lymph Node (N) Status | The presence or absence of non-nodal regional metastases (i.e., microsatellites, satellites or in-transit metastases) is categorized in the N-category criterion based upon the number (if any) of tumor-involved regional lymph nodes. |

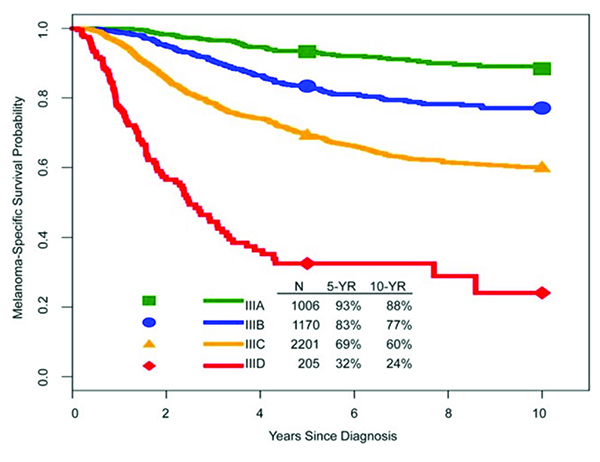

| AJCC Prognostic Stage III Groups | Stage III groupings have been redefined and increased from three to four subgroups, with the addition of a stage IIID subgroup. Stage III disease is associated with heterogeneous outcomes; five-year melanoma-specific survival rates range from 93 percent for stage IIIA disease to 32 percent for stage IIID disease. |

| Definition of Distant Metastatis (M) | The site of distant metastasis remains the primary component of the M category: non-visceral (distant cutaneous, subcutaneous, nodal), M1a; lung, M1b; non-central nervous system (CNS) visceral, M1c; and a new M1d designation for metastases involving the CNS. M1c no longer includes CNS metastasis. Although an elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is no longer an M1c criterion, LDH remains an important predictor of survival in stage IV and is now recorded for any M1 anatomic site of disease. |

Table 1. Revisions to the Melanoma TNM Melanoma Staging Systema

aUsed with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Eighth Edition, New York: Springer International Publishing; 2017 (Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, ed. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Eighth Edition, New York: Springer International Publishing; 2017:563-585).3

Changes in Stages I to III Melanoma

In the eighth edition of the AJCC staging system, the Melanoma Expert Panel focused on evidence-based revisions of stages I to III melanoma. These changes were based on analyses of an updated International Melanoma Database, which included de-identified patient records from 10 institutions in the United States, Europe and Australia for over 46,000 patients with stages I through III melanoma who had received treatment since 1998. The data reflect contemporary clinical practice. Thus, clinically node-negative patients with T2 to T4 melanoma were included only if they had undergone sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), while those with T1 melanoma were included with or without undergoing SLNB. With more accurate nodal staging and risk stratification, there was evidence of stage migration between the seventh and eighth editions of the AJCC staging system, as survival outcomes for patients with similar stage groups were generally greater in the eighth edition.

The T Category Criteria

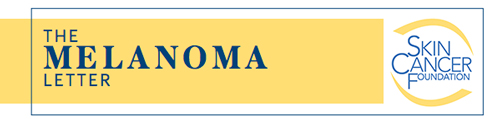

Breslow tumor thickness

In the eighth edition, the T category continues to be defined by melanoma thickness thresholds of 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 mm (Table 2 and Figure 1a-b). Several previously published studies have suggested that survival among patients with T1 melanoma is primarily related to tumor thickness, with a clinically important threshold in the region of 0.7 to 0.8 mm.5,6 In the eighth edition AJCC analyses of the T1 cohort,4 the panel evaluated survival outcome of a 0.8 mm tumor thickness threshold, primary tumor ulceration and mitotic rate (as a dichotomous variable, <1 mitosis per mm2 vs ≥1 mm per mm2). Multivariable analyses of factors predictive of melanoma-specific survival (MSS) revealed that, among patients with T1 melanoma, tumor thickness and ulceration were stronger predictors of MSS than mitotic rate. Based on these analyses, T1 subcategories were revised so that T1a tumors are nonulcerated melanomas <0.8 mm in thickness while T1b are melanomas 0.8 to 1.0 mm in thickness regardless of ulceration status or ulcerated melanomas <0.8 mm in thickness. Mitotic rate is no longer used to subcategorize T1 melanomas.

Ulceration

Ulceration is an adverse prognostic factor.7,8 Consistently across the 2001, 2008 and 2017 AJCC prognostic factor analyses, patients with ulcerated primary melanomas generally have MSS similar to those of patients with nonulcerated primary melanomas of the next highest tumor thickness category.2–4,9 In the eighth edition, as in the seventh, the absence or presence of ulceration is designated as “a” or “b”, respectively, in each T subcategory.

No longer a T1 criterion, mitotic rate should still be reported for all primary melanomas

In the eighth edition, though mitotic rate is no longer a T category criterion, it should be documented as a whole number (per mm2) for all patients, as it can impact prognosis for patients with stages I to III melanomas. Mitotic rate was removed as a staging criterion for T1 tumors because substratifying T1 tumors using a 0.8 mm cut point showed a stronger association with MSS compared to using presence or absence of mitoses as a dichotomous variable.4 Nonetheless, increasing mitotic rate among patients with clinically node-negative (cN0) primary melanoma was significantly associated with decreasing MSS in univariate analysis.4 Mitotic rate remains a major determinant of prognosis across tumor thickness categories and should be documented in all primary invasive melanomas.

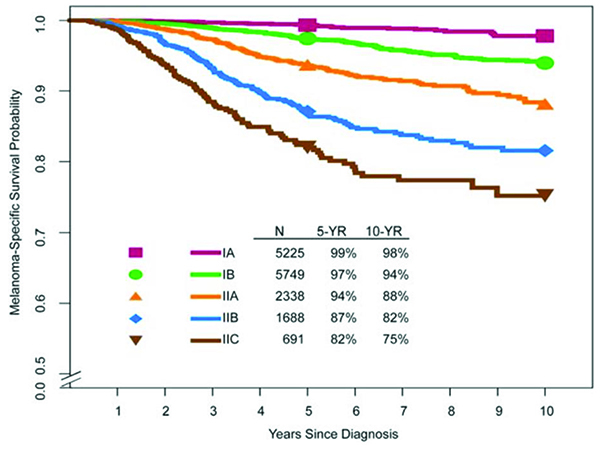

The N Category Criteria

The major changes to the N category in the eighth edition of the AJCC staging system pertain to stage groupings and the categorization of patients with non-nodal regional metastasis (Table 2 and Figure 1c-e).

Regional lymph node metastasis

The N category delineates the number of tumor-involved regional nodal metastases and the presence or absence of non-nodal regional metastases. Patients without clinical or radiographic evidence of regional lymph node metastasis but who have tumor-involved regional nodal metastasis after a sentinel node biopsy are defined as having “clinically occult” nodal metastasis and represent the majority of patients who present with regional metastasis at diagnosis.1 Patients with clinically or radiologically detected regional nodal metastases are defined as having “clinically detected” nodal metastasis and have worse survival than those with clinically occult regional metastases.4 Patients with clinically occult (N1a, N2a, N3a) and clinically detected (N1b, N2b, N3b) regional lymph node metastases without microsatellites, satellites or in-transit metastases are subcategorized based on the number of tumor-involved nodes.

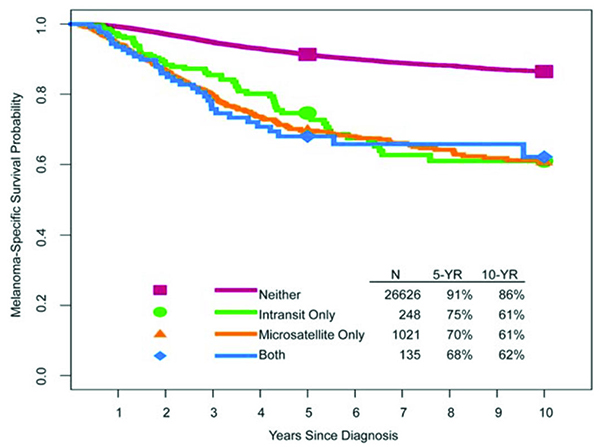

Non-nodal regional metastasis

Microsatellites, satellites and in-transit metastases are associated with similar survival outcomes (Figure 1d). In the AJCC eighth edition, microsatellites are defined as any microscopic focus of metastatic tumor cells in the skin or subcutis adjacent or deep to but discontinuous from the primary tumor.3 Satellite metastases are classically defined as any foci of clinically evident cutaneous and/or subcutaneous metastases occurring within 2 cm of but discontinuous from the primary melanoma. In-transit metastases are defined empirically as clinically evident cutaneous and/or subcutaneous metastases occurring >2 cm from the primary melanoma in the region between the primary melanoma and the regional lymph node basin.

In the eighth edition AJCC international melanoma database, there was no difference in survival outcome among these entities in univariate analysis, and they thus were grouped together for staging purposes (Figure 1d).4 Patients with microsatellite, satellite and/or in-transit metastases are categorized as N1c, N2c, or N3c based on the number of tumor-involved regional lymph nodes.4,10

The M Category Criteria

There are no stage groupings in the eighth edition AJCC melanoma staging system for patients with distant (stage IV) melanoma metastasis. Stage IV subcategories are defined by both anatomic site of metastatic disease (M1a, M1b, M1c and M1d) and the serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level obtained at the time of stage IV diagnosis.

Central nervous system (CNS) disease defines a new M subcategory, M1d

In the new staging system, M category definitions are based on both anatomic site of distant metastatic disease and serum LDH level for all anatomic site categories (Table 3). Patients with distant metastasis to the skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle or distant lymph nodes are categorized as M1a and have a relatively better prognosis compared with patients who have distant metastases located in other anatomic sites.11–13 Patients who have lung metastasis (with or without concurrent skin or subcutaneous metastases) have an intermediate prognosis and are categorized as M1b. Those with metastasis to any other visceral sites (excluding the CNS) have a relatively worse prognosis and are categorized as M1c. A new M category (M1d) was added to account for the overall poor prognosis associated with CNS disease as well as to enhance clinical trial design and analysis.4

LDH no longer defines M1c disease

Although patients with an elevated LDH level no longer automatically categorize to M1c, elevated serum LDH remains an important prognostic factor and identifies stage IV patients with a lower survival rate based upon multiple prospective analyses.14–19 Serum LDH is designated within each M category anatomic site based on whether LDH is elevated (designated “0” for “not elevated” and “1” for “elevated” level).

Table 2. AJCC Eighth Edition T Category, N Category and Pathological Stage Groups for Stages I to III Cutaneous Melanomaa,b

Stage Groupings Based on TNM Categories

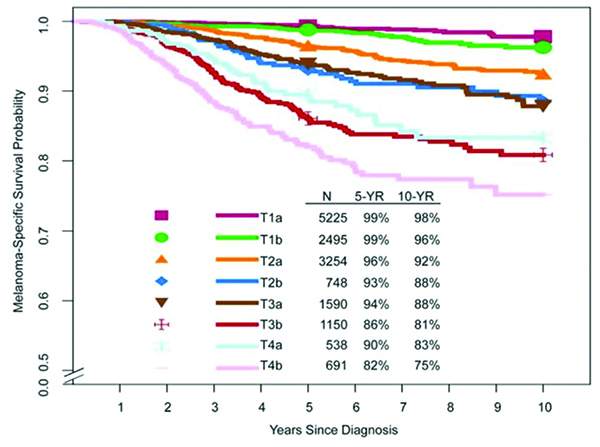

Stages I and II disease

Patients with stages I and II melanoma have localized disease, while those with stages III and IV melanoma have regional and distant metastatic disease, respectively (Table 2 and Figure 1). Although partially defined by the absence of regional disease, patients with stage II melanoma with high-risk features (such as greater tumor thickness and presence of ulceration) may have a worse prognosis than patients with primary melanoma with more favorable features and limited occult regional metastatic (stage IIIA) disease. For example, patients with stage IIC melanoma have worse expected five-year and 10-year survival than those with stage IIIA disease (82 percent and 75 percent versus 93 percent and 88 percent, respectively).

Heterogeneity of stage III disease

In the eighth edition, there are four stage III subgroups based on tumor thickness, ulceration status and number of tumor-involved lymph nodes (and whether these were clinically occult versus clinically detected), as well as the presence or absence of non-nodal regional metastases (Table 2). There are significant differences in prognosis across the four stage III subgroups (Figure 1e), with five-year MSS ranging from 93 percent for stage IIIA to 32 percent for stage IIID disease.4 These rates are significantly better compared with five-year MSS for stages IIIA, IIIB and IIIC disease in the seventh edition (78 percent, 59 percent and 40 percent, respectively), and will have a significant impact on clinical decision-making, patient counseling and clinical trial design.

Stage IV disease

There are no stage groupings for stage IV melanoma.

The Importance of Regional Lymph Node Staging

The importance of nodal staging and the ultimate benefits of SLNB (sentinel node biopsy) and CLND (completion lymph node dissection) have been a matter of long-standing discussion and debate, culminating in the recent results of two important long-running studies. Thus, we consider it important to include here a review on the topic of regional lymph node staging.

Regional lymph nodes represent the most common first site of metastasis in melanoma patients. Nodal staging is valuable for multiple reasons, including:

1) It can provide risk stratification and prognostication for patients at significant risk of harboring occult nodal metastases.

2) It can assist in selecting patients for adjuvant systemic therapies.

3) SLNB and CLND may improve regional disease control.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB)

The technique of lymphatic mapping and SLNB is associated with a low rate of complications (<5 percent) and has become a standard of care for staging clinically negative regional lymph node basins in patients deemed to have sufficient risk of occult nodal metastasis.20–22 The risk of sentinel lymph node (SLN) metastasis is very uncommon (<5 percent of cases) among patients with T1a melanomas,23 but rises with increasing primary melanoma thickness: five to 12 percent of T1b (<0.8 mm, ulcerated; 0.8-1.0 mm with or without ulceration) melanomas,4,23,24 and over 50 percent of T4b (>4.0 mm, ulcerated) melanomas.4

The Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial-I (MSLT-I)20,25 was a multi-institutional randomized controlled trial (RCT) comprised of 1269 patients with primary melanoma (≥1.0 mm thick or ≥ Clark level IV with any tumor thickness) randomized to wide excision and regional lymph node observation (with lymphadenectomy at time of nodal relapse) or to wide excision and SLNB with immediate CLND if tumor-involved nodes were identified on SLNB. In this study, patients with positive SLNs had worse five- and 10-year MSS compared with those who had negative SLNs; pathological SLN status was the strongest prognostic factor among all clinical and pathological factors studied. Overall, MSLT-I strongly supported the role of SLNB in early nodal evaluation and confirmed occult SLN involvement as a major prognostic factor associated with patient outcome.

Based on these and other data, the joint ASCO–SSO (American Society of Clinical Oncology–Society of Surgical Oncology) guideline panel recommends SLNB for patients with primary melanomas >1.0 mm.26 Both the ASCO-SSO and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines state that for patients with T1b (<0.8 mm with ulceration or 0.8-1.0 mm with or without ulceration) melanomas, SLNB may be considered and discussed with the patient.22,26

M Category |

M Criteria |

|

Anatomic Site |

LDH Level |

|

| M0 | No evidence of distant metastasis | Not applicable |

| M1 | Evidence of distant metastasis | |

| M1a | Distant metastasis to skin, soft tissue including muscles, and/or nonregional lymph node | Not recorded or unspecified |

| M1a(0) | Not elevated | |

| M1a(1) | Elevated | |

| M1b | Distant metastasis to lung with or without M1a sites of disease | Not recorded or unspecified |

| M1b(0) | Not elevated | |

| M1b(1) | Elevated | |

| M1c | Distant metastasis to non-CNS visceral sites with or without M1a or M1b sites of disease | Not recorded or unspecified |

| M1c(0) | Not elevated | |

| M1c(1) | Elevated | |

| M1d | Distant metastasis to CNS with or without M1a, M1b, or M1c sites of disease | Not recorded or unspecified |

| M1d(0) | Not elevated | |

| M1d(1) | Elevated | |

Table 3. Definition of Distant Metastasis (M)a

aUsed with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Eighth Edition, New York: Springer International Publishing, 2017 (Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin AB, Edge SB, Greene, FL, et al. (Eds.) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Eighth Edition. New York: Springer; 2017:563-585).3

Regional lymphadenectomy in the post-MSLT-II era

Until recently, immediate completion lymph node dissection (CLND) has been the standard of care for patients with metastases in one or more SLNs. The goals of CLND among patients with clinically occult regional lymph node metastasis in the SLN have classically been to 1) increase accuracy of staging and assist in clinical decision-making with respect to adjuvant systemic therapy, 2) enhance regional disease control and reduce risk of distant spread of disease and 3) improve MSS.

Although CLND is associated with operative morbidity, such as lymphedema, there is staging value in knowing the non-sentinel nodal status (non-SLN). Multiple retrospective studies have reported that metastatic non-SLNs are an independent negative prognostic factor associated with higher recurrence rates following CLND as well as worse disease-free survival, MSS and overall survival.27–29 Other studies have demonstrated that the risk for non-SLN metastasis increases as the tumor burden in the sentinel node increases, and exceeds 25 percent if the sentinel node metastatic tumor measures 2 mm or greater.30–32

Two multicenter randomized controlled trials (DeCOG-SLT, MSLT-II)33,34 were designed to address the question of whether immediate CLND in patients with nodal metastases identified by SLNB improves survival compared with nodal observation. DeCOG-SLT33 was a multicenter RCT in which patients with a positive SLNB were randomized to either immediate CLND (N=242) or observation (N=241), with distant metastasis-free survival as the primary endpoint. The sample size of this trial is relatively small and the follow-up is relatively short at 35 months. The MSLT-II trial randomized 1934 patients with SLN metastases to either immediate CLND or nodal observation with ultrasound.

In the follow-up period, neither trial demonstrated an overall survival difference between patients undergoing immediate CLND and those undergoing nodal observation. However, CLND was associated with a slightly higher rate of disease-free survival at three years (68 percent versus 63 percent, p=0.05) and a higher disease control rate in the regional nodes at three years (92 percent versus 77 percent, p<0.001). It is also important to note that in both studies, two-thirds of patients enrolled had a low tumor burden (≤1 mm) in the SLNs. Thus, some have opined that there was a selection bias of patients at lower risk of metastatic non-SLNs.

One logical conclusion of the results is that the SLNB itself may have been therapeutic and sufficient to achieve regional disease control in some patients, and furthermore, that many of those patients with non-SLN metastases also had a higher risk of harboring distant metastases that would negate a putative survival benefit from CLND. As evidence for this conclusion, patients who underwent CLND and were found to have metastatic non-SLNs had a lower MSS compared with patients whose non-SLNs were free of metastases. The MSLT II investigators concluded that “immediate CLND increased the rate of regional disease control and provided prognostic information but did not increase MSS among patients with melanoma and sentinel node metastases.”34

The current NCCN guidelines22 state: “For patients with a positive SLN, two phase 3 studies have demonstrated no improvement in MSS or overall survival in patients undergoing CLND compared to those who underwent active nodal surveillance. CLND did provide additional prognostic information as well as improvement in regional control/recurrence at the expense of increased morbidity.” Thus, the NCCN guidelines recommend either active nodal basin surveillance or CLND for patients with a positive SLNB: “CLND of the involved nodal basin should be discussed and offered” to patients, depending upon the probability of non-SLN metastases, the morbidity of the procedure and the staging value of CLND on adjuvant systemic therapy or clinical trial enrollment.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier melanoma-specific survival curves from the eighth edition international melanoma databasea according to:

(a) T subcategories

(b) pathological stage I and II subgroups

(c) N subcategories

(d) the presence or absence of microsatellites, satellites and/or in-transit metastases

(e) pathological stage III subgroups

aAdapted and used with permission from Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Eighth Edition. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67:472-492.4

Figure 1. (a) T subcategories

—————————————————————

Figure 1. (b) Pathological stage I and II subgroups

—————————————————————

Figure 1. (c) N subcategories

—————————————————————

Figure 1. (d) Presence or absence of microsatellites, satellites and/or in-transit metastases

—————————————————————

Figure 1. (e) Pathological stage III subgroups

Conclusions

A standardized and contemporary cancer staging system is essential for meaningful comparisons to be made across patient populations, while accurate staging and risk stratification are important to guide patient treatment and for the selection of patients for clinical trials. The eighth edition of the AJCC melanoma staging system incorporates several notable revisions of the seventh edition. These were derived from the analysis of a large international melanoma database and reflect our contemporary understanding of the natural history of metastatic melanoma and the clinical management of patients with cutaneous melanoma. The AJCC eighth edition cutaneous melanoma staging system was formally implemented in the United States on January 1, 2018.

References

- Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Edge S, Byrd D, Compton C, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Seventh ed. New York: Springer Verlag; 2009.

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(36):6199-6206.

- Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin M, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Eighth ed. Switzerland: Springer; 2017:563-585.

- Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67(6):472-492.

- Gimotty PA, Elder DE, Fraker DL, et al. Identification of high-risk patients among those diagnosed with thin cutaneous melanomas. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25(9):1129-1134.

- Green AC, Baade P, Coory M, et al. Population-based 20-year survival among people diagnosed with thin melanomas in Queensland, Australia. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(13):1462-1467.

- Balch CM, Murad TM, Soong SJ, et al. A multifactorial analysis of melanoma: prognostic histopathological features comparing Clark’s and Breslow’s staging methods. Ann Surg 1978; 188(6):732-742.

- Balch CM, Wilkerson JA, Murad TM, et al. The prognostic significance of ulceration of cutaneous melanoma. Cancer 1980; 45(12):3012-3017.

- Balch CM. Melanoma of the the skin. In: Greene F, Page D, Fleming I, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Sixth ed. New York: Springer Verlag; 2002.

- Read RL, Haydu L, Saw RPM, et al. In-transit melanoma metastases: incidence, prognosis, and the role of lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22(2):475-481.

- Barth A, Wanek LA, Morton DL. Prognostic factors in 1,521 melanoma patients with distant metastases. J Am Coll Surg 1995; 181(3):193-201.

- Brand CU, Ellwanger U, Stroebel W, et al. Prolonged survival of 2 years or longer for patients with disseminated melanoma. An analysis of related prognostic factors. Cancer 1997; 79(12):2345-2353.

- Cochran AJ, Bhuta S, Paul E, Ribas A. The shifting patterns of metastatic melanoma. Clin Lab Med 2000; 20(4):759-783.

- Kelderman S, Heemskerk B, Van Tinteren H, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase as a selection criterion for ipilimumab treatment in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2014; 63(5):449-458.

- Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Efficacy and safety in key patient subgroups of nivolumab (NIVO) alone or combined with ipilimumab (IPI) versus IPI alone in treatment-naive patients with advanced melanoma (MEL) (CheckMate 067). Eur J Cancer 2015; 51(Supp 3):S664-665.

- Long GV, Weber JS, Infante JR, et al. Overall survival and durable responses in patients with BRAF V600-mutant metastatic melanoma receiving dabrafenib combined with trametinib. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(8):871-878.

- Weide B, Martens A, Hassel JC, et al. Baseline biomarkers for outcome of melanoma patients treated with pembrolizumab. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22(22):5487-5496.

- Long GV, Grob J-J, Nathan P, et al. Factors predictive of response, disease progression, and overall survival after dabrafenib and trametinib combination treatment: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17(12):1743-1754.

- Nosrati A, Tsai KK, Goldinger SM, et al. Evaluation of clinicopathological factors in PD-1 response: derivation and validation of a prediction scale for response to PD-1 monotherapy. Br J Cancer 2017; 116(9):1141-1147.

- Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(7):599-609.

- Wong SL, Faries MB, Kennedy EB, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and management of regional lymph nodes in melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol December 2017: JCO2017757724.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Version 1.2018. Date accessed: 12/29/17. Melanoma. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/melanoma.pdf.

- Han D, Zager JS, Shyr Y, et al. Clinicopathologic predictors of sentinel lymph node metastasis in thin melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(35):4387-4393.

- Andtbacka RHI, Gershenwald JE. Role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin melanoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2009; 7(3):308-317.

- Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(13):1307-1317.

- Wong SL, Balch CM, Hurley P, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology joint clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(23):2912-2918.

- Leung AM, Morton DL, Ozao-Choy J, et al. Staging of regional lymph nodes in melanoma: a case for including nonsentinel lymph node positivity in the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. JAMA Surg 2013; 148(9):879-884.

- Pasquali S, Mocellin S, Mozzillo N, et al. Nonsentinel lymph node status in patients with cutaneous melanoma: results from a multi-institution prognostic study. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(9):935-941.

- Reintgen M, Murray L, Akman K, et al. Evidence for a better nodal staging system for melanoma: the clinical relevance of metastatic disease confined to the sentinel lymph nodes. Ann Surg Oncol 2013; 20(2):668-674.

- Van Der Ploeg APT, Van Akkooi ACJ, Haydu LE, et al. The prognostic significance of sentinel node tumour burden in melanoma patients: an international, multicenter study of 1539 sentinel node-positive melanoma patients. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50(1):111-120.

- Egger ME, Bower MR, Czyszczon IA, et al. Comparison of sentinel lymph node micrometastatic tumor burden measurements in melanoma. J Am Coll Surg 2014; 218(4):519-528.

- Gershenwald JE, Andtbacka RHI, Prieto VG, et al. Microscopic tumor burden in sentinel lymph nodes predicts synchronous nonsentinel lymph node involvement in patients with melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26(26):4296-4303.

- Leiter U, Stadler R, Mauch C, et al. Complete lymph node dissection versus no dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node biopsy positive melanoma (DeCOG-SLT): a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17(6):757-767.

- Faries MB, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Completion dissection or observation for sentinel-node metastasis in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(23):2211-2222.